Game Sage: machine learning enters Mushroom Kingdom

Game Sage; a machine learning recommendation system for video games.

Introduction

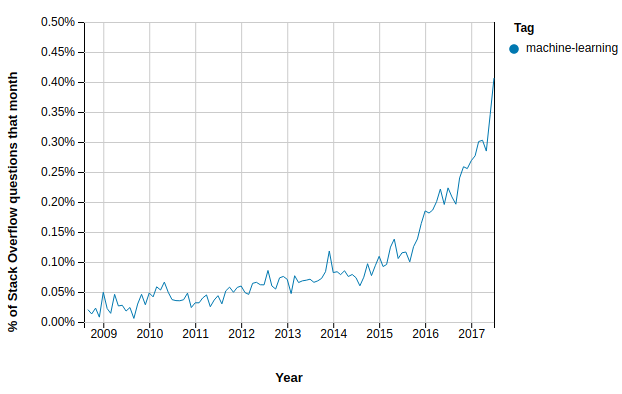

It’s no secret that machine learning is becoming a dominant force in the tech industry. From central heating to fighting terrorism, machine learning is becoming ubiquitous. Instead of watching it all fly by, I was keen to see what all the hype was about and give it a go for myself.

If you’re looking for ground-breaking machine learning research, then you should stop reading now. If, on the other hand, you’re curious to see how you can start learning about machine learning and apply it to a problem you’re interested in, then keep reading…

Problem

As I’ve mentioned in other posts before, I’m a big video game fan. Leading a busy London lifestyle, I don’t always get that much time to play these days, but when I do, I want to be sure I’m going to like what I’m playing. Aside from reading reviews, I sometimes want to find a game that is similar to previous games I’ve played before. There are a few lesser-known websites out there dedicated to this, but I thought I would give this a shot myself.

Recommender

Before I even began to investigate which machine learning techniques might be applicable to the problem, I had to get hold of the data. As I’m sure many machine learning experts will tell you, obtaining high quality data is crucial to the success of your model. Fortunately, the folks over at Giant Bomb offer a huge amount of user-created video game data from their REST API. The API has detailed information on over 58k games and is free to use for non-commercial purposes. Below is a subset of the data you can obtain related to a game.

{

"id": 49973,

"name": "Horizon Zero Dawn",

"genres": [

{

"id": 5,

"name": "Role-Playing"

},

{

"id": 43,

"name": "Action-Adventure"

}

],

"themes": [

{

"id": 3,

"name": "Sci-Fi"

},

{

"id": 18,

"name": "Post-Apocalyptic"

}

],

"concepts": [

{

"id": 207,

"name": "Open World"

},

{

"id": 2287,

"name": "Female Protagonists"

}

],

"locations": [

{

"id": 1323,

"name": "Colorado"

}

],

"platforms": [

{

"id": 146,

"name": "PlayStation 4",

"abbreviation": "PS4"

}

],

"developers": [

{

"id": 2392,

"name": "Guerrilla Games"

}

]

}

I loaded the data in JSON format into a local instance of PostgreSQL, where I would be able to query it offline at a later stage.

Now the task was to research which machine learning approaches would be most applicable for a recommender system. There has already been a huge amount of effort put into this problem by lots of tech giants (Netflix and Amazon to name just a few), so I wasn’t expecting to compete with them, but was nonetheless curious to see how far a relatively simple approach could get me.

Due to the contraints of the data, this would have to be an unsupervised learning technique; there was no training data since I didn’t have a list of “correct” recommendations. Therefore, I would simply be trying to group similar games together, which is also known as clustering. One very popular method for clustering is k-means.

k-means clustering works by partitioning your n entities into k clusters. The algorithm starts by placing k random centroids in Euclidean space, these will eventually become the centre for each cluster of games. It then iterates through every entity, calculating a distance metric (more on this later) between the entity and each centroid. The entity then gets assigned the cluster for which the distance metric is the lowest. After this initial iteration, the algorithm recomputes the centroid’s value based on the average of the entities that ended up in the cluster. This process keeps repeating itself, until either convergence is reached (subsequent iterations cause no changes to clusters) or some iteration limit is reached.

Conceptually, the algorithm made sense to me, but I was unsure how I would calculate the “distance” between games and a centroid. Fortunately, I stumbled across an excellent Python example that makes use of the scikit-learn library. It uses a TDIDF (term frequency–inverse document frequency) approach to provide a statistic for how important a word in a given context is. In the context of video games, this could be the different names of genres that appear in our data set. A sparse matrix is then produced where each column represents a word and each row represents a game and the values of the matrix are the TDIDF weighted scores. Now that the words have been translated into a matrix, we can compute a Euclidean distance between an entity and a centroid by taking the square root of the sum of squared differences for each word.

I tried out this approach by creating a TDIDF word vector with the genres of each game.

# vectorize the genres

vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer(input='content', analyzer='word', lowercase=True)

v = vectorizer.fit_transform(map(lambda game: game.genres, games))

# cluster

km = KMeans(n_clusters=40)

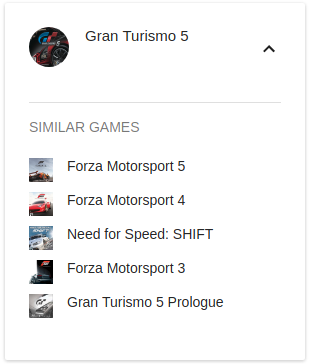

This gave some initially promising results, but it struggled to differentiate between games that were similar in genre but themetically quite different, for instance, Gran Turismo and Mario Kart. I knew I had to include some more features from the game dataset, but wasn’t entirely sure how I would combine these features to good effect. Once again scikit-learn saved the day, as they provide a FeatureUnion class, which helps you combine different features with appropriate weights.

features = FeatureUnion(

transformer_list=[

('genre', genre_pipeline),

('theme', theme_pipeline),

('concept', concept_pipeline),

('location', location_pipeline),

('developer', developer_pipeline),

('platform', platform_pipeline),

],

transformer_weights={

'genre': 1,

'theme': 0.4,

'concept': 0.4,

'location': 0.1,

'developer': 0.2,

'platform': 0.2,

}

)

x = features.fit_transform(games)

km = KMeans(n_clusters=n_clusters, max_iter=10000, tol=1e-5)

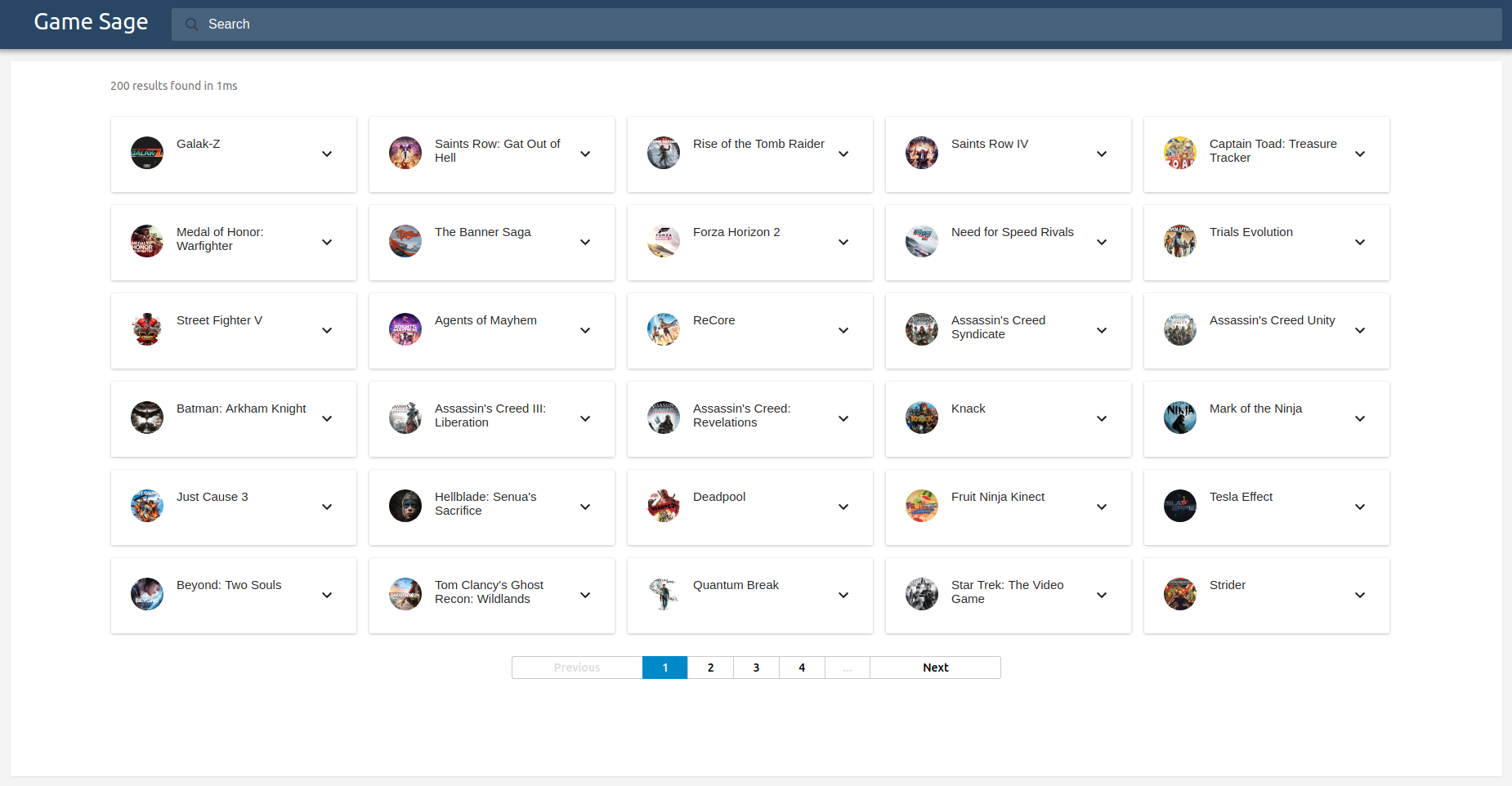

With the additional features, I appeared to be getting reasonable results, although the only way of verifying the clusters was for me to check them manually. To speed things up, I decided I would build a lightweight front-end to display the results. Using a combination of Elasticsearch and React, I created the web app shown below.

This helped me verify the clustering results until I settled upon a set of roughly optimal feature weights.

Game Over

The results I produced were far from world-class, but the whole exercise helped me to become more familiar with the world of machine learning. It would be interesting to see how far I could get with a supervised model (if I could obtain the training data), but I’ll save that for another day. I hope this has shed a little bit of light on the elusive world of machine learning.